HKU and UCLA Scientists Uncover the Mechanism powering “Space Battery” above Auroral Regions

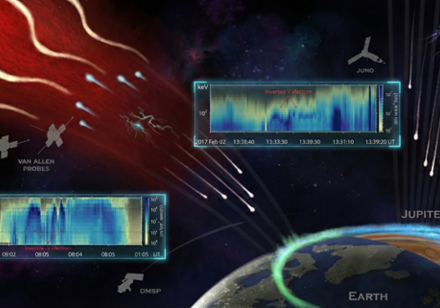

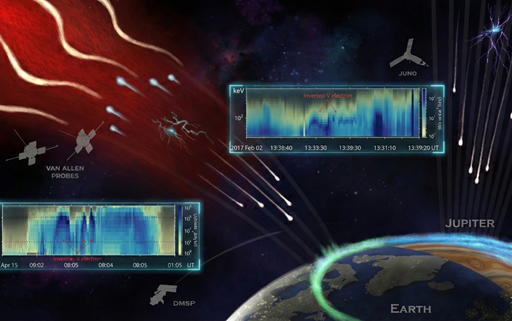

The dazzling lights of the aurora are created when high-energy particles from space collide with Earth’s atmosphere. While scientists have long understood this process, one big mystery remained: What powers the electric fields that accelerate these particles in the first place? A new study co-led by the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at The University of Hong Kong (HKU) and the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) now provided an answer. Published in Nature Communications, the research reveals that Alfvén waves — plasma waves travelling along Earth’s magnetic field lines — act like an invisible power source, fueling the stunning auroral displays we see in the sky. By analysing how charged particles move and gain energy in different regions of space, the researchers demonstrated that these waves act as a natural accelerator, supplying energy that drives charged particles down into the atmosphere and produces the glowing auroral lights. To confirm their findings, the team analysed data collected by multiple satellites orbiting Earth, including NASA's Van Allen Probes and the THEMIS mission. The data provided solid evidence that Alfvén waves continuously transfer energy to the auroral acceleration region, maintaining the electric fields that would otherwise dissipate. “This discovery not only provides a definitive answer to the physics of Earth’s aurora, but also offers a universal model applicable to other planets in our solar system and beyond,” said Professor Zhonghua YAO of the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at HKU. Professor Yao leads a dedicated team in space and planetary science at HKU, which has established a reputation for high-impact research on planetary auroras. With deep expertise in the magnetospheric dynamics of planets like Jupiter and Saturn, the HKU team brought a critical planetary perspective to the study. “Our team at HKU has long focused on the auroral processes of giant planets. By applying this knowledge to the high-resolution data available near Earth, we have bridged the gap between Earth science and planetary exploration.” Professor Yao added. The research represents a model of interdisciplinary collaboration. The UCLA team, led by Dr Sheng TIAN, contributed extensive expertise in Earth’s auroral physics, while the HKU team provided the broader context of planetary space physics. The full research paper can be read here. Caption: Comparative schematic of auroral acceleration processes on Earth and Jupiter. The electron spectrum for the Earth was from DMSP F19 spacecraft, and the one for Jupiter was from Juno spacecraft. Both spectra exhibit a similar inverted V-shaped structure, indicating the presence of stable electric potential drops above the auroral regions. This similarity points to a common auroral acceleration mechanism across planets and illustrates how insights from planetary aurorae help interpret high-resolution observations near Earth. Image credit: S. Tian and Z. Yao

NEWS DETAIL

Internationally Renowned Mathematician Professor Van H. Vu Joins HKU

The Department of Mathematics at The University of Hong Kong has welcomed Professor Van Ha VU, a world-leading mathematician whose research has shaped modern combinatorics, probability, and random matrix theory. Professor Vu received his PhD from Yale University in 1998 and was previously a full professor there. Before that, he held academic positions at the University of California, San Diego and Rutgers University. He is internationally recognised for solving several landmark problems in mathematics, including the Erdős–Folkman problem in number theory with Endre Szemerédi, the Shamir conjecture in random graph theory with Anders Johansson and Jeff Kahn, and together with Terence Tao, the circular law conjecture and four-moment theorem in random matrix theory. Random matrix theory plays a foundational role in quantum physics, complex systems, and artificial intelligence, where large random matrices are used to model quantum behaviour, analyse massive datasets, and understand the stability and performance of modern algorithms. Professor Vu’s work has helped establish the theoretical framework underlying these calculations. His honours include the George Pólya Prize in 2008, the Delbert Ray Fulkerson Prize in 2012, and an invitation to speak at the International Congress of Mathematicians in 2014, reflecting his standing among the world’s leading mathematicians. At HKU, Professor Vu will further strengthen the University’s research capacity in pure and applied mathematics, foster international collaboration, and contribute to the training of the next generation of mathematical scientists at a time when deep theoretical insight is increasingly vital to science and technology.

NEWS DETAIL