01 Mar 2022

Reconstructing How Dinosaurs Fed and Grew

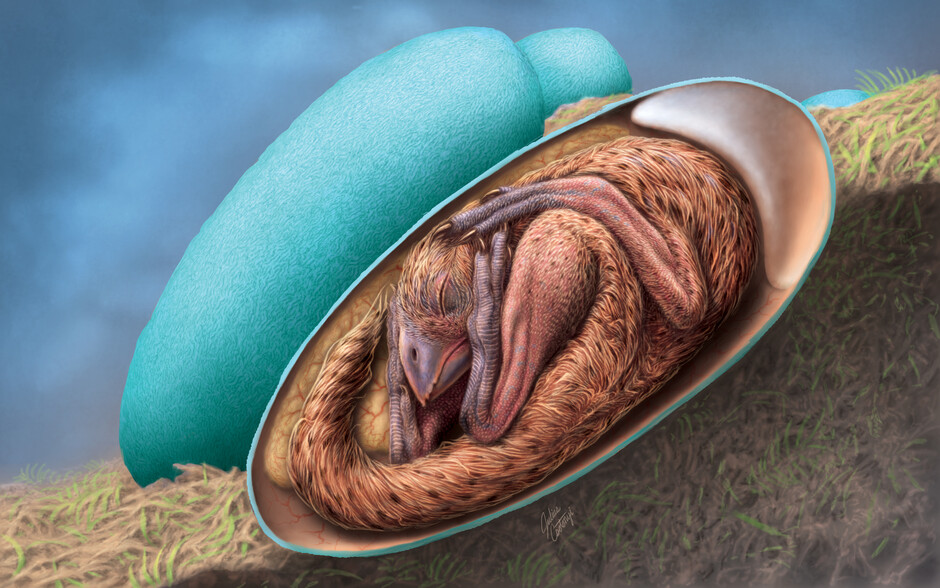

An artist’s reconstruction of a baby oviraptorosaur in its egg. Image: Julius Csotonyi/Handout

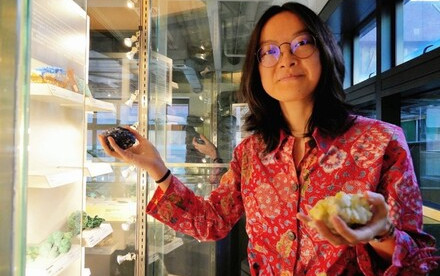

Fion Wai Sum MA

2019 - present PhD candidate in Earth Sciences (Palaeobiology), University of Birmingham

2017 - 2018 Master by Research in Palaeontology and Geobiology, The University of Edinburgh

2013 - 2017 Bachelor of Science, double major in Geology and Ecology & Biodiversity, HKU

Vertebrate palaeontology research

Vertebrate palaeontology is more than digging up and describing bones, but the study of total biodiversity and transitions in the history of life.

More than 99% of the species ever lived on Earth are extinct. However, these extinct organisms are exceedingly important to our understanding of the total biodiversity and transitions in the history of life. As a researcher in vertebrate palaeontology, Fion Wai Sum MA uses fossil record to study evolutionary processes in vertebrate history.

Non-avian dinosaurs are ideal models for studying macroevolutionary changes. They dominated the global terrestrial ecosystems for over 150 million years before they went extinct ~66 million years ago. One of Fion’s major lines of research is the dietary evolution of vertebrate animals. In a recent study, she used digital modelling and biomechanical analysis to study the feeding mechanics of theropod dinosaurs. Theropods are a group of dinosaurs that started off as carnivores and underwent significant dietary changes ¾ from carnivory to more specialised carnivory and herbivory. The team compared the feeding adaptations of carnivores and herbivores, and revealed that the jaws of all study groups became structurally stronger as they evolved through time.

Baby Yingliang measures 10.6 in (27 cm) long from head to tail and rests inside a 6.7 inch-long egg at the Yingliang Stone Nature History Museum in China.

Dinosaur embryo was about to hatch!

Recently Fion co-led an international team to study the oviraptorosaur ‘Baby Yingliang’ ¾ one of the best-preserved dinosaur embryos ever discovered. Oviraptorosaurs are theropod dinosaurs closely related to birds and thus are instrumental in tracing the origin of modern avian features. The team suggested that the bird-like posture of ‘Baby Yingliang’ may indicate a similar prehatching behaviour in oviraptorosaur and modern bird embryos, and that the avian tucking behaviour could have originated among dinosaurs. Again, this shows that the features previously thought unique to modern birds, could have first evolved among their dinosaurian ancestors.

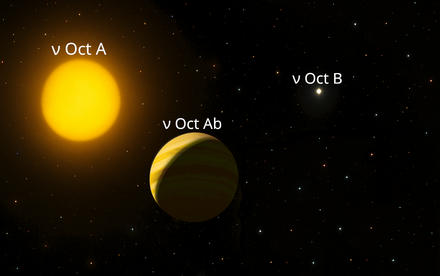

Fion applied digital modelling and functional analysis to study the feeding mechanics of theropod dinosaurs. Credit: Gabriel Ugueto.

With her background in CT-scan-based imaging and 3D reconstruction, Fion has been collaborating with pterosaur specialists to study the fossils from northeastern China. In 2021, the international team named two new species of pterosaurs from the Jurassic, namely Sinomacrops bondei and Kunpengopterus antipollicatus. The latter, dubbed ‘Monkeydactyl’, represents the oldest record of an opposed thumb in the Earth’s history.

Hong Kong-born palaeontologist ‘hatched’ from HKU Science

During her time as an undergraduate at HKU, Fion was supported by a Summer Research Fellowship and an Overseas Research Fellowship to gain her first research experience. For two summers, Fion was under the supervision of palaeontologist Dr Michael PITTMAN. She conducted research locally and at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP), Chinese Academy of Sciences. ‘I still remember how excited I was when I first entered the IVPP in Beijing. There were so many dinosaur fossils in the storage and I was delighted to be given the chance to study some of them,’ she said. With growing interest in this field, Fion decided to pursue postgraduate study and work towards becoming a vertebrate palaeontologist.

After PhD graduation, Fion would like to continue her research career and use new techniques to further explore topics on vertebrate dietary evolution and dinosaur growth. ‘Vertebrate palaeontology is more than digging up and describing bones. This field is rapidly changing and increasingly interdisciplinary. As a palaeontologist, I need to keep track of the latest development in palaeontology, as well as the technological advances in other fields such as ecology, engineering and medical and veterinary sciences.’ By applying complementary techniques, Fion hopes to address palaeontological questions from new perspectives and contribute to our understanding of the history of life. Regarding the future plan, she admits palaeontology is an uncommon subject area with limited career opportunities in academia. ‘Sometimes I do feel uncertain about my career path, but I try to be open to possibilities, be proactive and equip myself for any arising opportunities,’ she added.

As a Hong Kong-born palaeontologist, Fion hopes to come back to Hong Kong for research development if there is an opportunity. ‘Hong Kong would serve as a great base station for my research because East Asia is home to many vertebrate fossils, especially dinosaurs, and I have ongoing collaborations with several institutions in China,’ she said. The diversity of local universities provides a good platform for intra- and inter-institutional, cross-disciplinary collaboration. The high connectivity of Hong Kong with the other parts of the world also facilitates overseas fieldwork and museum visits. Although no dinosaur fossils are known, Fion wishes to study the fossils of Hong Kong alongside her research on vertebrate palaeontology. ‘I hope to study local palaeontology and stratigraphy by conducting fieldwork. Hong Kong has a geological history of over 400 million years with diverse fossils, including vertebrates, invertebrates, plants and microfossils. And I would like to contribute to enriching it,’ she added.