26 Mar 2021

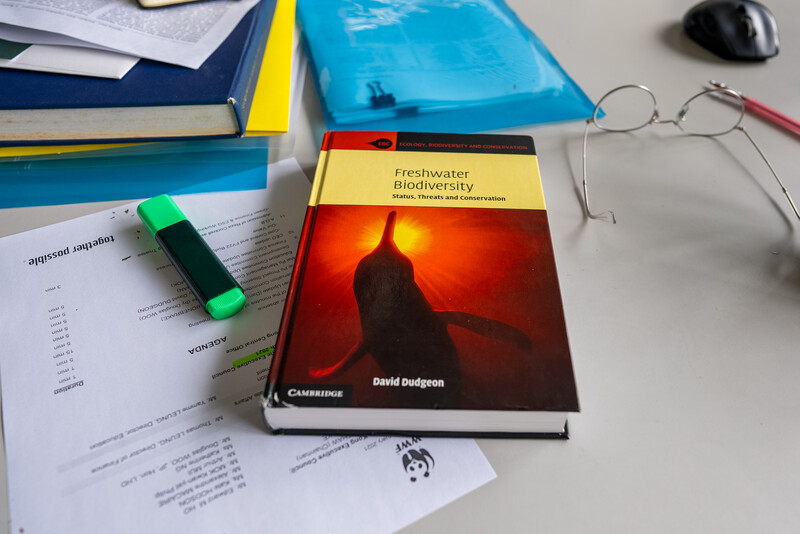

Interview: Professor David Dudgeon speaks about his latest book - Freshwater Biodiversity – Status, Threats and Conservation

Climate change will increase human demands for water, as we will need more water to grow food in a hotter world.

Last year, Professor David DUDGEON, Emeritus Professor of School of Biological Sciences, released a book “Freshwater Biodiversity – Status, Threats and Conservation”. The book is an urgent call to protect our freshwaters - lakes and rivers that we rely on for drinking water and to irrigate crops, and whose fisheries are actually larger than the sea fisheries.

In the book, his 9th, Dudgeon explains why lakes and rivers, that amount to less than 1% of our planet’s surface area but are home to almost 9% of the world’s species, are far more fragile than marine and terrestrial ecosystems. He tells of the extent of damage and exploitation the freshwaters have suffered – much greater than what the humanity has inflicted on land and in the sea.

With quotes from Leonardo da Vinci to Shakespeare and Greta Thunberg, and headings such as “Have all the Bigger Freshwater Fishes Really Had Their Chips?”, the book is a wealth of hard-hitting facts: that, according to population trend data, freshwater animals have declined by 81% since the 1970 - far more than those on land or in the oceans, and that about a third of all freshwater species are now endangered.

Dudgeon concludes the book with a warning that, despite climate change threatening to wreck our freshwater ecosystems beyond repair, there are still no adequate international strategies or targets to protect the planet’s lakes and rivers.

P: Dr Pavel TOROPOV from Research Division of Ecology and Biodiversity and School of Biological Sciences

D: Professor David DUDGEON from Research Division of Ecology and Biodiversity and School of Biological Sciences

P: What made you write this book?

D: In 2006 I was a coordinator of a review article published by Cambridge University Press, which said - look, tigers and whales and corals are threatened by humans, and almost everyone knows that, but nobody cares about freshwater biodiversity! That article became very widely cited and Cambridge University Press asked me – can you expand it into book? It was around 2008-2009 when I committed to writing it, but I found there was a lot to say. I didn’t finish until 2019.

P: Why are freshwater ecosystems so vulnerable, more so than terrestrial or marine ecosystems?

D: Fresh waters are embedded within human-dominated landscapes and are the receivers of any insults affecting (the surrounding) terrestrial systems. Also, humans take out or divert the medium that freshwater animals need to live - this does not happen to sea water.

Most fresh water animals have tiny ranges (a single lake or river basin), and so are more easily driven to extinction by a single event, say an episode of pollution, than their land- or sea-based counterparts.

Climate change will increase human demands for water, as we will need more water to grow food in a hotter world. So freshwater critters are more at risk from climate change that most other animals, given the dual problem of changing water availability and warming. Plus, if you are in an isolated lake or an east-west flowing river, you do not have the option of moving north into cooler climes.

Freshwater is also a multiuser resource for which humans compete. A factory owner using a river for waste disposal 'competes' with a farmer who wants that water for irrigation, as well as with those who need good quality water to sustain fisheries or as a source of potable water. Someone building a dam upstream of any of these users also will compromise the availability of water for others. After all this competition among human users there is not much left over for nature.

P: Yet freshwaters tend to be overlooked by the public and the conservationists, why is that?

D: People are distracted about leopards, tigers - all those wonderful animals that live on land!

When you look at David Attenborough documentaries, there is just one episode in the original Life on Earth series that deals with freshwater. When people think of life in the water, (for them) it means life in the sea; freshwater does not get a look in!

What proportion of world fisheries occur in the oceans and in freshwater? (The answer is) Half and half, actually slightly more in freshwater. The Mekong (river) alone provides 10% of the world’s (total) fishery yields!

But most people think that all the fish live in the sea! That’s not the case, but most of the fish living in freshwater are small - because the big ones have long since been fished out - dull-coloured species, but people disregard them in favour of gaudy marine coral fish and tasty groupers.

P: Hong Kong’s freshwater biodiversity does not get mentioned often.

D: There is a lot of freshwater biodiversity in Hong Kong: over 100 species of dragonflies, 25 amphibians, more than 70 freshwater fishes, including some endemic species that are found nowhere else in the world. And there are freshwater crabs and shrimps, and a host of aquatic insects.

P: You discovered several new species in Hong Kong, including a new species of fish – Hong Kong paradise fish, correct?

D: I 'discovered' the Hong Kong paradise fish in a local marshland some years ago, although I did not initially conclude that it was an entirely unknown species. That judgement was made by two German ichthyologists and they named it Macropodus hongkongensis.

(In Hong Kong) I've also described a new dragonfly and some mayflies and caddisflies, but I guess that is of much less interest! And I had some new species of bugs and beetles (found in Hong Kong) named after me.

P: Why does not the plight of tropical freshwater fisheries that you describe in your book, get far less attention, compared to the problems of European sea fishermen?

D: To be honest, this is because those affected are poor people of colour. Also, they often catch small fish - these freshwater fisheries are largely beneath the radar, in Europe anything in a lake or river that is not salmon, is not a fish worth eating. But (in tropical freshwater fisheries) many fish eaten are small fish, that are consumed whole or fermented and used as fish paste or garnish.

P: In the book, you go through all the threats to freshwaters – overexploitation, river regulation, but the largest chapter is about invasive species – 90 pages.

D: Yes, I got a little carried away there, but some people take a view that invasive species are the most pernicious threat to biodiversity.

Freshwaters are more vulnerable to invasives than marine ecosystems, because freshwaters are like islands surrounded by land, and each island is not saturated with respect to species. That could mean that there is space for invasive species to get in there, and there is not necessarily a species in the ecosystem that can parasitize and kill that invader.

I don’t think you can go out and eliminate the invasives, with very few exceptions. Invasion, lie extinction, is forever. Invasives tend to do well in systems that we have degraded or shifted from natural state. Unless we can restore them, the native species have little chance to recover.

P: Do Aichi Biodiversity targets (set by the UN’s Convention on Biodiversity in 2010) or the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals cater for freshwater?

D: There is no Aichi target referring specifically to protecting life in fresh waters. But there certainly should be one! The ‘Life below water’ Sustainable Development Goal refers solely to oceans, and could be extended to cover freshwater animals.

P: What would you set as new targets to protect freshwater biodiversity?

D: Maintaining the flow of rivers, maintaining longitudinal connection and mimicking the natural seasonal ups and downs in flow in some way. We also need to have something about sustainable exploitation of living resources – fishes, frogs, and so on.

One thing I did not touch on in this book - we are unsustainably removing sand from rivers for use in making concrete for building. It is happening in the Mekong Delta, it is happening in the Yangtze, and all over India. We must stop over exploiting the non-biological part of the environment too.

Then it is the question of controlling water pollution, and of somehow managing invasive species. You need a black list of the species people are not allowed to bring in to countries where they may become a nuisance.

We know what we need to do. But the willpower to do it is not there!

P: In the book you call the loss of species due to human action “morally repugnant”, and say that if we ever want biodiversity to be considered in decision making, loss of species must be considered as such.

D: This is from a talk I gave in Liverpool about freshwater biodiversity - I said: “we need to stand up and say to those who make the decisions - this loss of species is morally repugnant!” And I thought: “Am I going out on a limb here?” But I got applause and some people then posted it on Twitter. Or so I heard, I am too old to do social media.

P: A quote from your book: “it is a challenge to remain optimistic about the future of freshwater biodiversity”. Are you hopeful?

D: Before I wrote this book, I would give talks on this, and someone would always come up to me and say: “You depressed me so much!” I thought I managed to avoid being overly pessimistic in this book, although I tried to be realistic. Anyway, my answer is - I am not hopeful, but I am optimistic!

Article by Dr Pavel Toropov from Research Division of Ecology and Biodiversity and School of Biological Sciences

| |

A typical family catch on the River Marañón in Peruvian Amazonia. Small fish account for large part of freshwater fisheries' landings. Image: Pavel Toropov | European sturgeon used to be found in rivers across Europe, reaching lengths of up to 6 metres. Now the species is critically endangered. Large freshwater fish are becoming increasingly rare worldwide. Image: Hans Braxmeier / Pixabay |

| |

Hong Kong paradise fish – a new species discovered in Hong Kong by Professor Dudgeon. Image: David Dudgeon | Red-eared sliders, originally from North America, are one of the world's worst invasive animal species, and are frequently the subject of misguided mercy releases in Hong Kong. Image: Alan Leung |

|  |

The Mekong River is not only the worlds’ largest inland fishery, but also accounts for 10% of combined global fisheries. It is the source of protein for millions of people. Image: Richard Mcall / Pixabay | Water hyacinth is one of the most destructive invasive plant species. It that can quickly overgrow freshwater habitats, smothering the water surface and impeding oxygen exchange. Image: nguyenhuungli / Pixabay

|

| |

Freshwaters, such as the Yangtze River that flows through the Chinese megapolis of Chongqing, are embedded within terrestrial ecosystems and receive a massive impact from the surrounding human activity. Image: Sicheng Yang / Pixabay | The Hoover Dam in the USA. Dams are highly damaging to the functioning of river ecosystems. Image: RJA1988 / Pixabay |

|  |

Professor Dudgeon’s latest book – “Freshwater Biodiversity – Status, Threats and Conservation” took ten years to complete. Image: Alex Reshikov | Professor David Dudgeon in his office. Image: Alex Reshikov |