09 Feb 2020

HKU marine ecologists and international team unveils the historical impacts of development on coral reef loss in the South China Sea, suggesting possible coral restoration in Hong Kong

Researcher(s) drilling coral under water.

New research led by The University of Hong Kong, Swire Institute of Marine Science in collaboration with Princeton University and the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry highlights the historical impacts of development on coral reef loss in the South China Sea. The findings were recently published in the journal Global Change Biology.

Using cutting-edge geochemical techniques pioneered by their Princeton collaborators, the team extracted minute quantities of nitrogen from coral skeletons, which grow in observable layers of growth similar to tree rings. Although more than 99% of the skeleton is calcium carbonate, the coral secretes a protein scaffolding upon which the minerals are attached. In this way, corals can control their calcification which increases in productive summer months and decreases in cool winter months leading to a tell-tale alternation of high and low density bands. Those bands were observed and measured using x-ray equipment at the Ocean Park veterinary hospital.

Using coral cores archived at The University of Hong Kong, and spanning research laboratories at HKU, Princeton, and the Max Planck Institute, the team, led by SWIMS postdoctoral fellow Dr Nicolas Duprey extracted skeletal material from each band to reconstruct a nearly 200-year time-series of change in the Pearl River Delta that pre-dated British colonization. The coral – still living as of 2007, had continuously recorded the conditions of its environment during that period of time by utilizing resources from seawater to build new skeleton. Nitrogen, a key component of the protein scaffolding, is one such element derived from the corals diet. Coincidentally, nitrogen also bears tell-tale signs of human disturbance through the increasing prevalence of sewage pollution and a rapidly changing landscape in the Pearl River catchment within Guangdong Province.

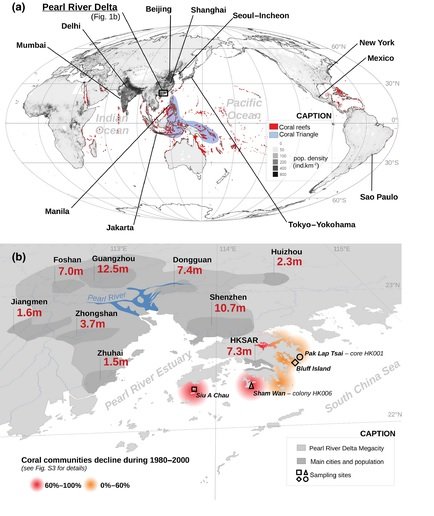

The well-documented collapse of southern Hong Kong coral communities in the 1980-1990s remained a mystery for the scientific community until now. The authors report that during the coral’s lifespan, the human population within the multi-city megalopolis sky-rocketed some 3,000% to today’s ~100 million people. Modern records showed that especially in the 1980s-1990s, during Hong Kong’s rapid development and the reclamation of Victoria Harbour, water quality deteriorated substantially which coincided with severe losses of local coral reefs, especially in western waters.

“The precise detective work that our team has led over the last 5 years allowed us to identify the main culprit of this loss: water quality! This is a very interesting find because often time global warming is pointed out as the cause of coral decline worldwide; we often feel helpless facing this scenario because it involves changing drastically everybody’s lifestyle on the planet to fix the problem. However, in the Pearl River Delta, the threat is different and originates from our poor handling of waste water treatment locally. Paradoxically, this is a good news because it implies that the solution to this problem is in our hands. Indeed, the improvement in waste water treatment in the 2000’s was recorded in our coral skeleton, indicating that these efforts must be continued if we want corals to come back in Hong Kong, ” said lead author Dr Nicolas Duprey.

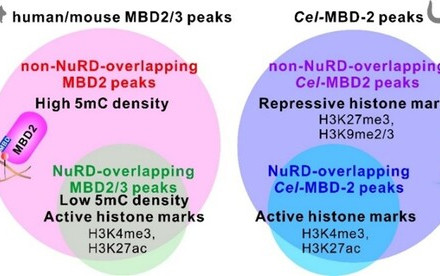

Moreover, the coral skeleton revealed that in that specific timeframe a major anomaly in the nitrogen isotope ratio occurred. This was an indication that the source of nitrogen the coral used to build its skeletal scaffolding became was replaced by pollution. To verify this, the researchers also measured the isotope values from museum specimens held by the Smithsonian Institution and Yale Peabody Museum that were collected in Hong Kong in the 1800s during some of the first global biodiversity expeditions.

The open-access study, led by Associate Professor Dr David Baker and SWIMS postdoctoral fellow Dr Nicolas Duprey was funded by the Environment and Conservation Fund. NN Duprey, XT Wang, T Kim, JD Cybulski, HB Vonhof, PJ Crutzen, GH Haug, DM Sigman, A MartínezGarcía, DM Baker (2019) Megacity development and the demise of coastal coral communities: evidence from coral skeleton δ15N records in the Pearl River Estuary. Global Change Biology.

Figure 1: The urban development on the world's coastlines is a rising threat for coral reefs. (a) The map shows the population density (source: CIESIN, 2017), the world's megacities (source: UN, 2018), coral reefs (source: UNEP‐WCMC, WorldFish Centre, WRI, TNC, 2010), and the world's hotspot of coral biodiversity, the Coral Triangle (Veron et al., 2011). (b) Detail map of the Pearl River Delta region showing the eight major cities composing the megacity and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) and their populations. The four sites sampled for this study are indicated with outlined symbols. The coral communities having experienced a major decline are highlighted in color. Maps were made with the geographic information software QGIS (www.qgis.com)

Image 3a & b: The museum specimens from the Smithsonian Institution and Yale Peabody Museum that were used for comparison of isotope values of coral skeleton. These specimens were collected in Hong Kong in the 1800s during some of the first global biodiversity expeditions.