Dr Alice Catherine HUGHES

Associate Professor of School of Biological Sciences

Research interests: conservation biology, OneHealth, species ecophysiology and distribution

Start date: December 8, 2021

1. What do you think are your most significant research accomplishments, and what has been the impact of your research?

My research broadly has two major different themes. One is on conservation approach which explores how threats impact on biodiversity at regional and global scales and tries to develop more pragmatic solutions to maintaining biodiversity. Outcomes of this work have been presented in global policy meetings, including drafting a policy brief for the state council in China on Greening the belt and road initiative. Another possible success of my work was the uplisting of all Japans Goniurosaurus gecko species to CITES appendix 3 shortly after we published our paper on global reptile trade and recommended the group as in particular need of protection due to their small populations and high risk of trade. Our work highlighted that up to 70% of animals in trade from some groups (such as lizards) come directly from the wild, meaning that urgent attention is needed to effectively protect these species from unsustainable and largely unregulated trade.

The other main strand of my research has focused more heavily on bats. Whilst I have worked on bats (especially across the Asian region) for over 15 years, largely focusing on regional ecology, since 2018 we started on bats and viruses with collaborators from Shandong Medical University. Following the onset of the early cases of SARS-COV2 our samples were sequenced in January 2020, revealing some of the closest viruses to SARS-CoV2 in bats. Since then, we collected more samples, revealing a suite of further coronaviruses including close relatives of both SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV2 in bats, even just within a single cave. This showed that Rhinolophus bats irrefutably are reservoirs of SARS-CoV2, though an intermediate host may have existed between bats and humans. This work has paved the way for some of the work we hope to do on OneHealth, managing landscapes to maintain healthy wildlife populations and minimising the risk of spillover between bats and other animals.

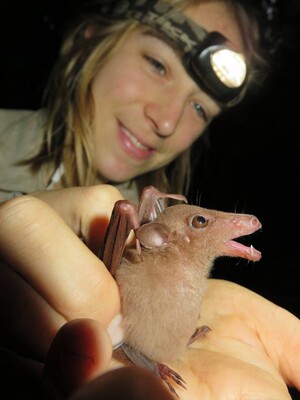

Releasing Hipposideros lylei in Myanmar.

Releasing Kerivoula hardwickii (a small insectivorous bat) in Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Yunnan, China

Surveying caves for bats in Northern Vietnam

2. Please tell us about one of your ongoing research projects that best reflect your visions in the scientific field.

Much of my work attempts to find pragmatic solutions to global issues around biodiversity loss. To this end, I have dedicated considerable time to testing various biodiversity and environmental datasets to assess their reliability and the limits of their sensible use. In one of our current projects, based on our former work on mapping biodiversity and various projects around developing frameworks and targets (such as ecological-conservation redlines and climate-biodiversity targets) into actionable policies which are supported by empirical data. These methods are important and finding synergies between different facets of the environment will be critical to gaining the necessary traction to deliver these targets. In some of our current work, we use a synergistic approach to identify potential biodiversity targets at countries currently at risk of defaulting on debt. Debt-for-nature swaps have been a tool applied to swap national debt for conservation in some countries. In the wake of covid, where many countries are at particular risk of both default and taking environmental shortcuts for economic gain, new solutions to protect biodiversity are needed. We identify and cost how potential unprotected biodiversity hotspots could be integrated into such a program to provide an economically viable way to conserve biodiversity in parts of the planet at the greatest risk of biodiversity loss.

3. What is the most important question you want to address?

How can we find economically viable ways to maintain biodiversity which can be mainstreamed through society.

As long as our work is theoretical and pathways to implementation are not outlined, we will continue to lose biodiversity. That is why in my research I attempt to be holistic, to understand the drivers of species loss, obtain reliable data on species distributions, and then use economically relevant analyses to develop solutions, and metrics to ensure that these can be monitored and measured. Holistic frameworks to enable us to better govern landscapes are essential, but it requires a detailed understanding of each component of the ecological system and it is human links, as well as the mechanisms responsible for its unsustainable use.

Surveying bat caves using bioacoustic detectors in Myanmar as part of my student (Ada Chornelia's) project on cryptic Rhinolophid bats in Southeast Asia.

4. Can you give an example of your translational work? How would you bridge the gap from your research-to-research users?

For each component of my work, that bridge is different. For conservation to be achieved, we need populations that care, meaning that even school syllabuses should reflect biodiversity and sustainable development. Thus, even as a child, I gave given presentations to schools and biodiversity to engage, inspire and educate, so they are motivated to care about biodiversity and more open to being responsible for their actions. As part of this outreach, I have written for various popular science columns, including ALERT Conservation and the conversation.

In addition, we need policymakers to have access to accurate and accessible research and data. I have so far drafted two policy briefs for the Chinese state council (one on greening the BRI and one on regulating wildlife trade to prevent future pandemics). I have also been an active participant of the CCICED biodiversity special policy study group.

Furthermore, international governance needs to reflect biodiversity needs at all scales. Through various NGOs and societies I work with, I have taken part and spoken in various UN conventions, including the Convention on Biodiversity (CBD), Wetlands (RAMSAR) and Wildlife Trade (CITES), and through both my NGO collaborations have engaged in discussions of the post-2020 global conservation framework, as well as developing or co-developing a number of motions for the IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature).

Lastly, as well as contributing to several books, including large volumes on the mammals of China, and smaller books such as one on understanding the impacts of infrastructure on biodiversity (for non-scientists), I have also led capacity-building workshops around the world on conservation, and spatial ecology to facilitate upcoming conservation scientists on the most appropriate techniques for spatial analyses in conservation. I am also a GBIF (Global Biodiversity Information Facility) data ambassador, promoting the sharing of biodiversity data, so it can feed into further analyses on biodiversity.

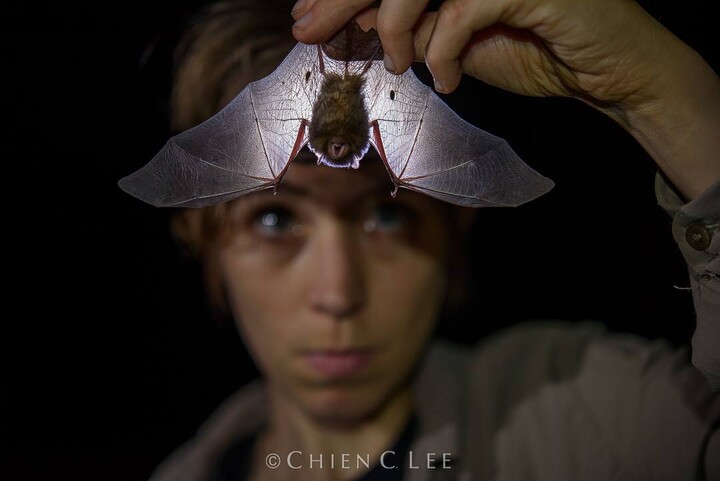

Releasing Macroglossus sobrinus (a small nectar bat) in Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Yunnan, China

5. Where do you see yourself in five years/ ten years? What do you want to accomplish the most?

I want to continue to play a role in global conservation and work more with UN organisations and NGOs as well as with organisations like Asia-Pacific Biodiversity Observation Network (APBON) to advocate for conservation approaches based on the best of data. One element of research which is currently in its infancy is the OneHealth research I am trying to do, which aims to integrate species ecology and ecophysiology into landscape management. By understanding how species demography and natural stressors intersect with the risk of spillover, and how managing the landscape across the year can mitigate this, we can considerably reduce the potential of spillover risks. Moving into the future, I hope that more of the tools and integrative approaches that I am developing now can be incorporated into policy and guidelines of practice to facilitate sustainable development. Engagement with organisations that can help translate my research into policy actionand also help provide data driven solutions for conservation and sustainable development.

6. What are the challenges you are facing?

Different elements of research have different challenges. Bat research has become challenging because the pandemic has heightened sensitivities around bats, and yet this data is needed to reduce the potential of pandemics into the future. In addition, whilst I have written various policy briefs, it is often hard to know how much gets translated into action, but with continued effort and collaborative work I hope to see further successes into the future