04 Sep 2018

Mismatch in timing of ivory bans in China and Hong Kong undermines the conservation of African elephants

A group of savanna elephants (Loxodonta africana) in Amboseli National Park, Kenya (Photo Credit: Alex Hofford/WildAid)

A new study has examined how recent ivory bans – and gaps thereof – could help or harm the preservation of elephants. Ivory trade has fueled the rampant and ongoing poaching of these important animals across Africa, leading to unprecedented population declines throughout much of the continent.

“The unabated slaughter of elephant populations has left much of Africa without this keystone species,” says Alex Hofford, coauthor with WildAid Hong Kong.

To combat this problem, China closed its ivory market at the end of 2017.

“This was a huge boost towards elephant conservation,” says Luke Gibson, the study’s lead author affiliated with the Southern University of Science and Technology (SUSTech) in Shenzhen, China and the University of Hong Kong (HKU). “China has traditionally held the largest demand for ivory products, and the closure of its ivory market could eliminate a large share of the threat towards African elephants,” he adds.

Hong Kong – a Special Administrative Region of China – made a parallel move in January this year by passing the Hong Kong Ivory Ban Bill, which will eventually prohibit all ivory trade inside its borders. However, the full ban won’t be implemented until the end of 2021, leaving a long gap in the regulation of this trade.

“Hong Kong is the global epicenter of wildlife trade, and so banning ivory sales here is a vital step,” says Alexandra Andersson, coauthor from HKU. “But this ban should be implemented immediately, otherwise elephant populations may continue to decline,” she adds.

The authors examined trends in government seizures of illegal ivory shipments in China and Hong Kong, to understand how the closure of one market could affect the other.

“Seizures of elephant ivory in China and Hong Kong are negatively correlated,” says Gibson. “Over the past two decades, when there was more ivory confiscated in China, there was less confiscated in Hong Kong…and vice versa,” he added. “So the closure of China’s market might push the trade to Hong Kong,” he worries.

This shift might already be happening. Last year Hong Kong intercepted the largest illegal shipment of elephant ivory since 1989 – when international trade of ivory was prohibited. Since then, only ivory from before the 1989 convention has been permitted for sale.

“This was the world’s largest ivory seizure, ever,” says Hofford, describing the more than seven metric tons intercepted in July 2017. “To us, this suggests the trade could already be already shifting to Hong Kong, which is concerning,” he adds.

“As long as ivory trade persists in Hong Kong, it enables the poaching of elephants across Africa by providing a legal market into which poached ivory can be laundered,” says Andersson. “The future of African elephants might depend on Hong Kong’s determination to end this trade, immediately.”

A group of savanna elephants (Loxodonta africana) in Amboseli National Park, Kenya (Photo Credit: Alex Hofford/WildAid).

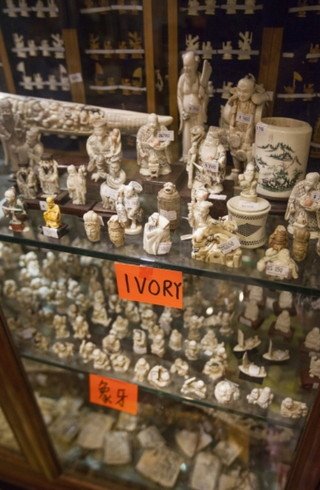

Processed elephant ivory on sale in a shop in Hong Kong, considered to be the global epicenter of wildlife trade (Photo Credit: Alex Hofford/WildAid)