18 Aug 2022

New global map of ant biodiversity reveals areas that may hide undiscovered species

This study helps to add ants, and terrestrial invertebrates in general, to the discussion on biodiversity conservation.

Ants are essential for the functioning of ecosystems as they play vital roles, from aerating soil to dispersing seeds and nutrients to scavenging and preying on other species. Yet a global view of their diversity is lacking.

Dr Benoit GUÉNARD of The School of Biological Sciences (SBS) of The University of Hong Kong (HKU) in collaboration with an international team of researchers from the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST), Japan, and multiple institutes around the world, has developed the first high-resolution map in the world that combines existing knowledge with machine learning to estimate and visualise the global diversity of ants. The study provided a ‘treasure map’ as a guide to explore new species and help conserve the global diversity of ants. The maps and dataset are presented in an article published in Science Advances.

An ant (species: Ectatomma tuberculatum) photographed in Costa Rica. Ants make up a large fraction of the total animal biomass in most terrestrial ecosystems, but researchers say that an understanding of their global diversity is lacking. This new study provides a high-resolution map that estimates and visualizes the global diversity of ants. Photo credit: Dr Benoit Guénard

They are hunters, farmers, harvesters, gliders, herders, weavers, and carpenters. They are ants, and they are a big part of our world, comprising over 14,000 species and a large fraction of animal biomass in most terrestrial ecosystems. Like other invertebrates, ants are important for the functioning of ecosystems. However, a global view of their diversity is lacking, which led to difficulties in identifying high diversity centres of invertebrates for future research.

As the co-first author, Dr Benoit Guénard from HKU SBS started this decade-long project with Professor Evan ECONOMO of OIST to create a database of occurrence records for different ant species from online repositories, museum collections, and around 10,000 scientific publications. Researchers around the world contributed and helped identify errors. More than 14,000 species were considered, which varied dramatically in the amount of data available.

‘The diversity of insects is phenomenal, representing more than half of all species on Earth. We thus needed to include insects into our global understanding of biodiversity and not to limit ourselves to vertebrate groups which are conspicuous and popular, but from which questioning existed about their representativeness of biodiversity more generally. For several reasons, ants were an ideal group for this’ said Dr Benoit Guénard of HKU SBS.

‘This study helps to add ants, and terrestrial invertebrates in general, to the discussion on biodiversity conservation,’ said Professor Evan Economo, who leads the Biodiversity and Biocomplexity Unit. ‘We need to know the locations of high diversity centres of invertebrates so that we know the areas that can be the focus of future research and environmental protection.’

Professor Economo added that the resource would also serve to answer a number of biological and evolutionary questions, such as how life diversified and how patterns in diversity arose.

However, while containing a description of the sampled location, the vast majority of these records did not have the precise coordinates needed for mapping. To address this, the team built a computational workflow to estimate the coordinates from the available data, which also checked all the data for errors, and they also made different range estimates for each ant species depending on how much data was available. For species with less data, they constructed shapes surrounding the data points. For species with more data, the researchers predicted the distribution of each species using statistical models that they tuned for optimal complexity.

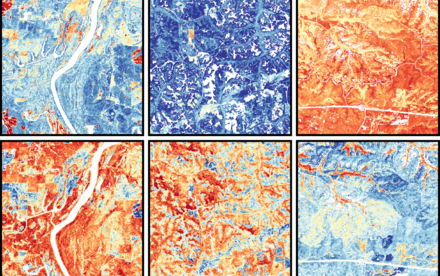

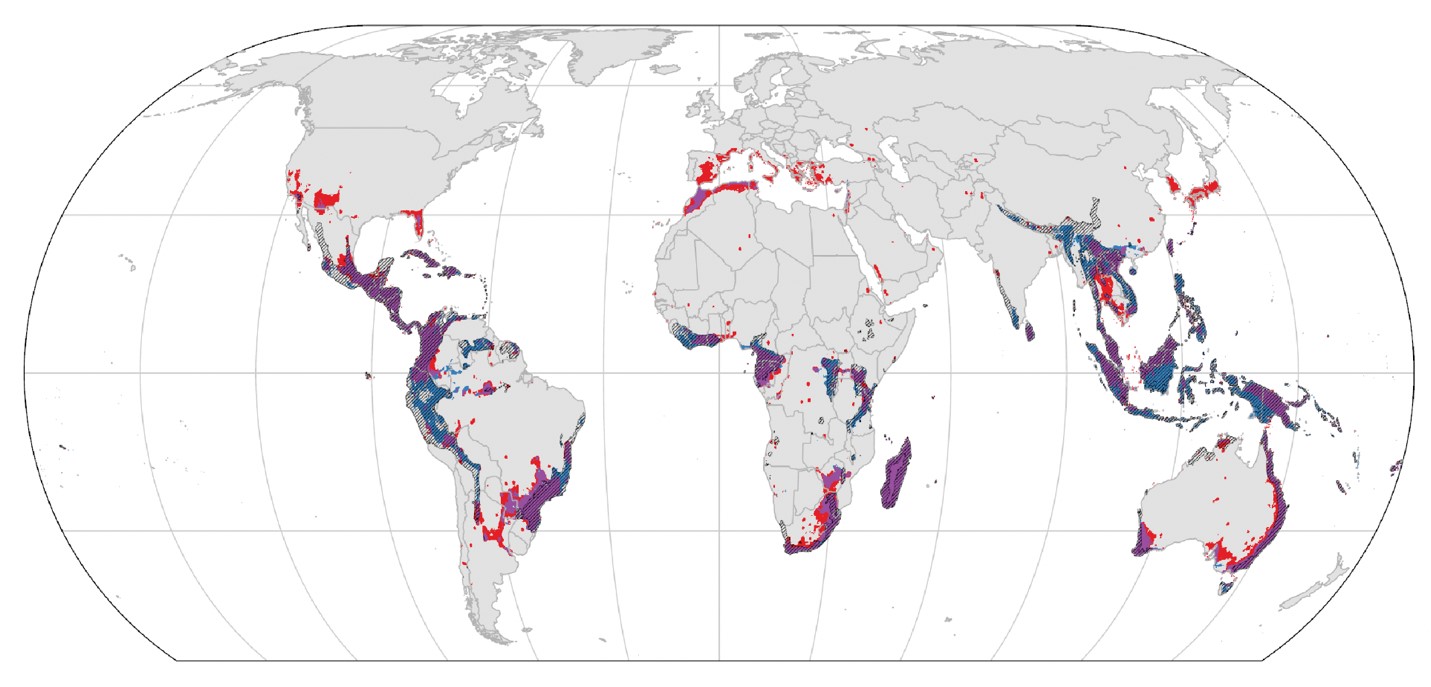

The researchers brought these estimates together to form a global map, divided into a grid of 20 km by 20 km squares, that showed an estimate of the number of ant species per square (called the species richness). They also created a map that showed the number of ant species with very small ranges per square (called the species rarity). In general, species with small ranges are particularly vulnerable to environmental changes.

However, there was another problem to overcome—sampling bias. So, the researchers utilised machine learning to predict how their diversity would change if they sampled all areas around the world equally and, in doing so, identified areas where they estimated many unknown, unsampled species exist.

A map highlighting species rarity—the areas with many ant species with very small ranges. The colored areas all indicate important regions for ant species with small ranges. Red indicates areas that are relatively more studied than other areas, which could artificially boost their importance. Purple areas are both important based on current knowledge and are likely to remain so after future sampling. Blue areas are predicted by machine learning to harbor concentrations of undiscovered, small-ranged ant species, giving scientists a treasure map to guide future exploration. This image is an edited version of figures that appear in the paper.

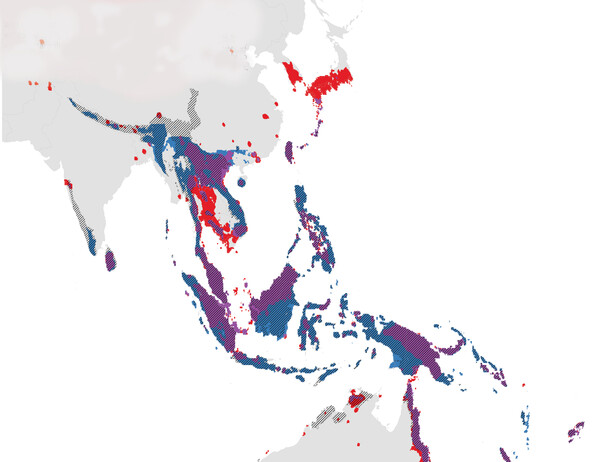

This map highlights ant biodiversity centers in Asia—areas that harbor many ant species with small ranges. The different colors indicate how the importance of each region may change with future research around the globe. Red areas are predicted to decrease in importance, purple areas will remain among the most important regions even after more areas are studied, and blue indicates areas that should be targets for exploration as they are predicted to harbor hidden diversity. This is a modified version of a figure in the paper.

Professor Economo said, ‘This gives us a kind of treasure map, which can guide us to where we should explore next and look for new species with restricted ranges.

When the researchers compared the rarity and richness of ant distributions to the comparatively well-studied amphibians, birds, mammals, and reptiles, they found that ants were about as different from these vertebrate groups as the vertebrate groups were from each other, which was unexpected given that ants are evolutionarily highly distant from vertebrates. This is important as it suggests that priority areas for vertebrate diversity may also have a high diversity of invertebrate species. But, at the same time, it is necessary to recognise that ant biodiversity patterns have unique features. For example, the Mediterranean and East Asia show up as diversity centres for ants more than vertebrates, and these are very important region for conducting future surveys and research.

Finally, the researchers looked at how well-protected these areas of high ant diversity are. They found that it was a low percentage—only 15% of the top 10% of ant rarity centres had some sort of legal protection, such as a national park or reserve, which is less than existing protection for vertebrates.

‘This work focused on the species already described, meaning known by Science, however, it is likely that as many ant species remain unknown to this day. Supporting research and infrastructures like museums that facilitate and accelerate the descriptions of this fully unknown part of diversity should be perceived as a top priority, especially within tropical regions where most of biodiversity is concentrated.’ concluded Dr Benoit Guénard.

This article was adapted from the original drafted by the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST), Japan.